Consumers routinely ignore the small print in contracts. It makes sense that we ignore fine print since we’re inundated with it when we buy software, join websites, or sign credit card agreements. Yet when it comes to commercial contracts, good transactional attorneys understand that ignoring the small print can lead to financial losses and significant inequity in business relationships.

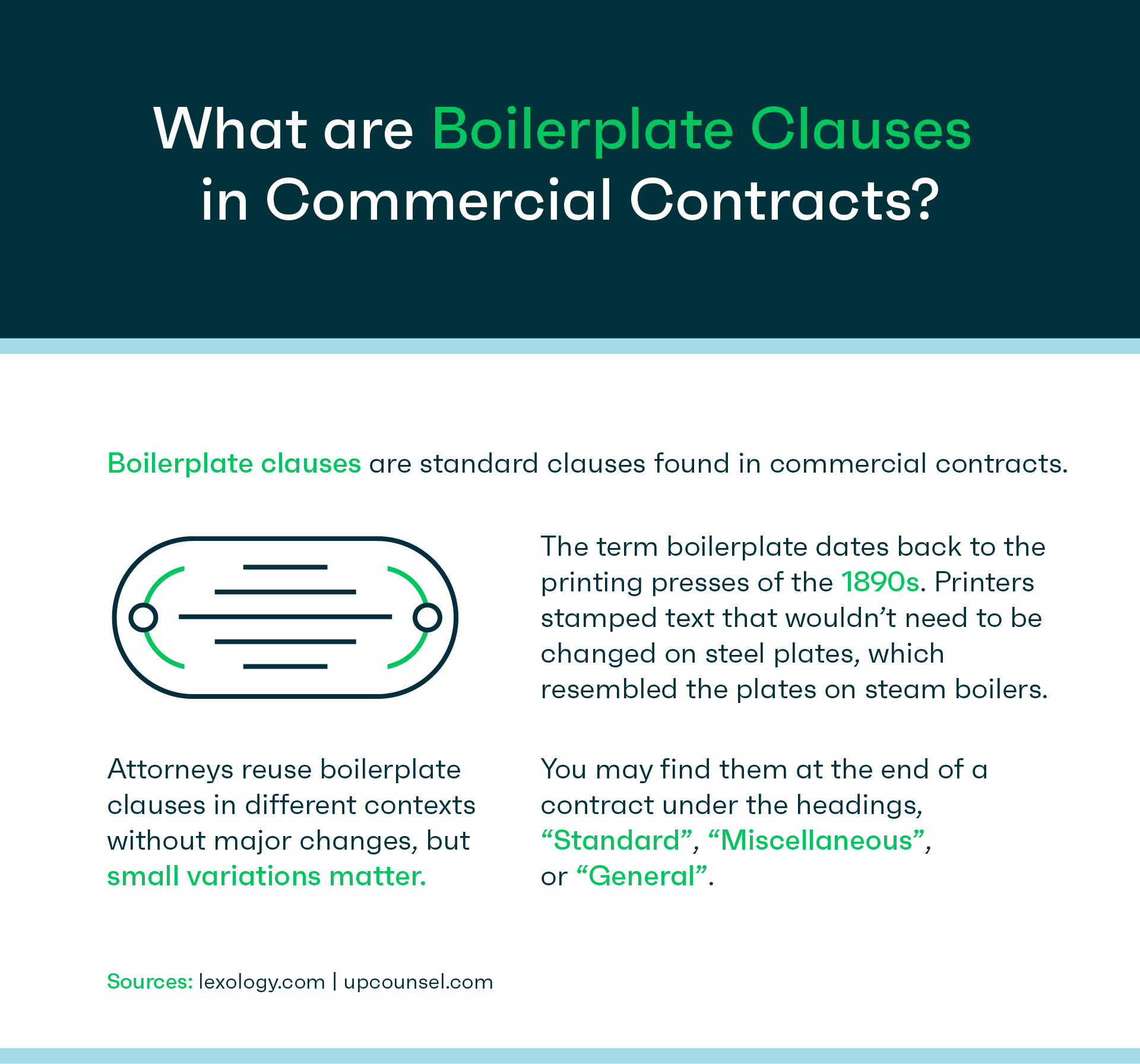

The small print of most commercial contracts includes boilerplate phrases, which require the same scrutiny as any other part of the agreement. What is a boilerplate clause in a contract? Boilerplate clauses are standard clauses found in most commercial contracts. Sometimes they appear in tiny print at the end of a purchase order, or they’re interspersed throughout a lengthy master agreement.

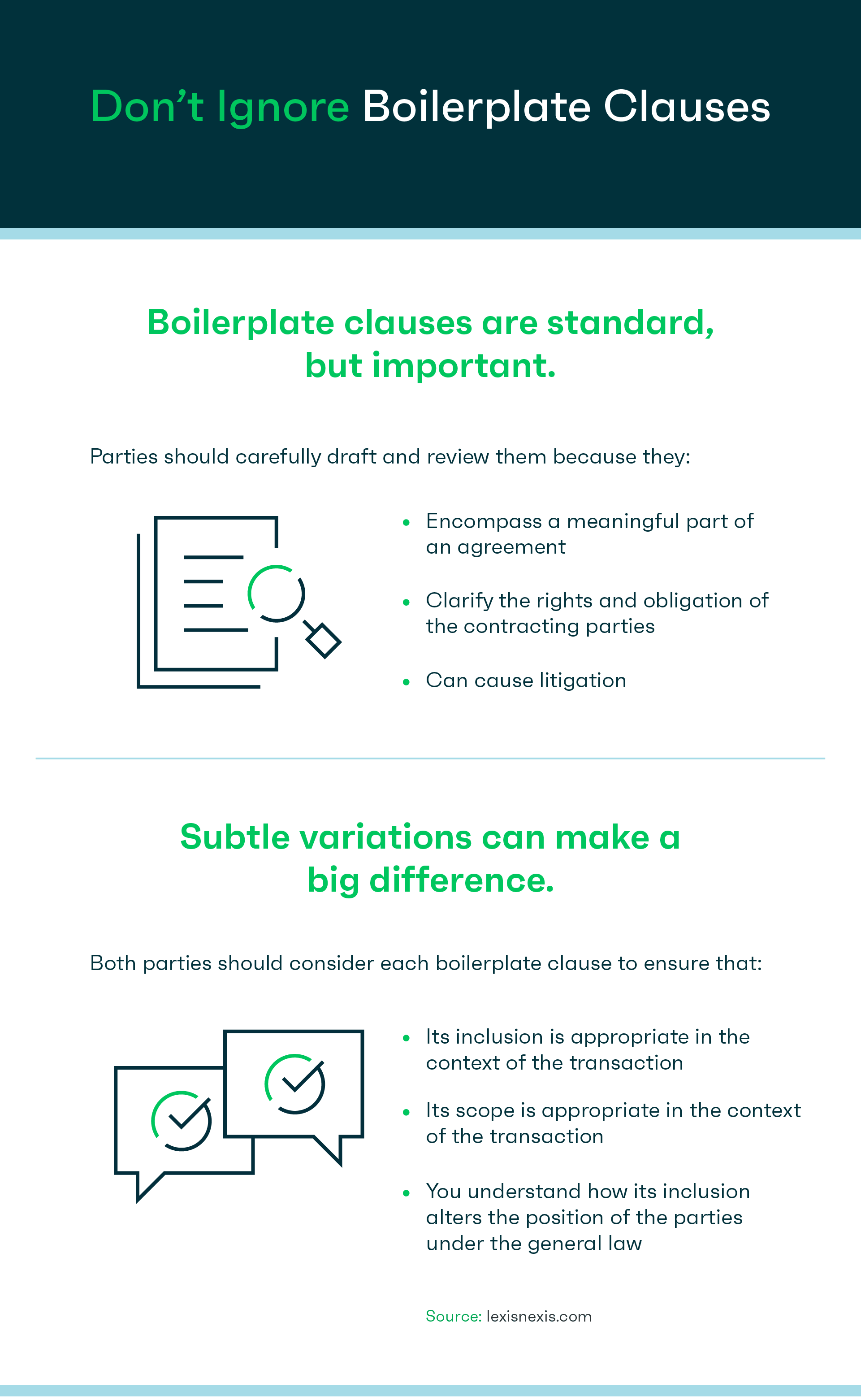

While boilerplate clauses are considered standard or general terms, parties should take care when drafting and reviewing them because they encompass a meaningful portion of every agreement. For instance, they spell out how the parties allocate risk and whether the parties protect trade secrets. Keep reading to find boilerplate clause examples, discover why you need to draft and review boilerplate language carefully, and get tips for which provisions to include.

Common Boilerplate Clauses

You’ll find the following clauses in many commercial contracts.

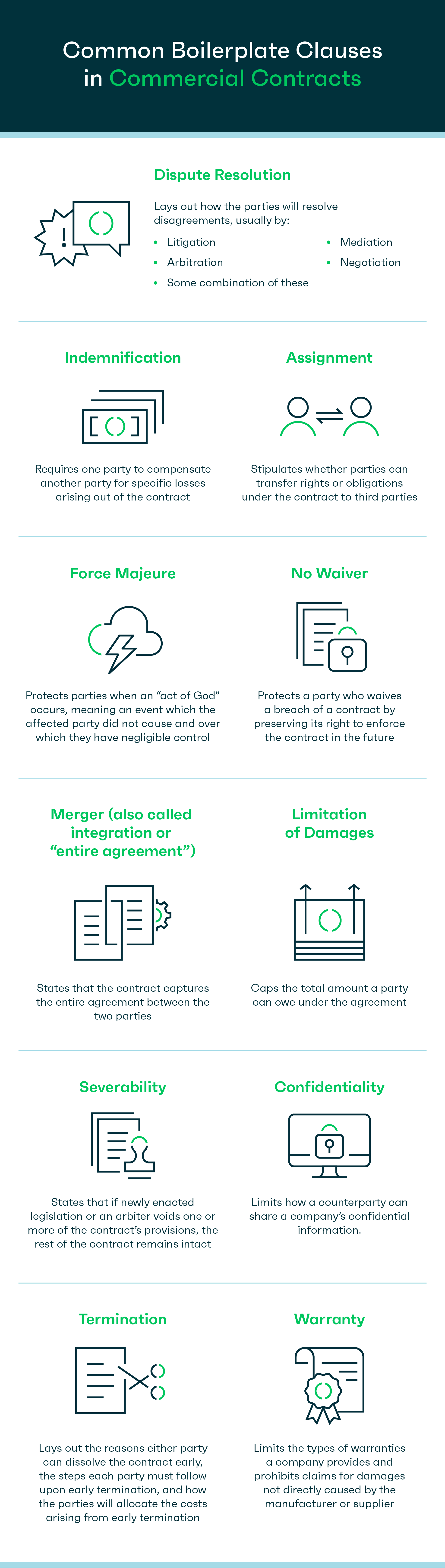

Dispute Resolution

The dispute resolution clause lays out how the parties will resolve disagreements that arise during the term of their agreement. Options can include litigation, arbitration, mediation, negotiation, or some combination of these.

Each option has benefits and disadvantages. To decide which to include, think about what aspects of dispute resolution are most important for your company. Negotiation and mediation are less contentious processes, but you may be forced to compromise too much. Litigation offers the option of a jury trial and subpoena power. But arbitration gives you more flexibility with the types of admissible evidence and may lead to a quicker resolution. Or you may want to combine several options. For instance, you could require the companies’ executives to engage in good faith negotiations before proceeding to arbitration.

Indemnification

Indemnity provisions require one party to compensate another party for specific losses relating to the contract. You should examine indemnification clauses carefully because they transfer some of the contractual risks from one party to the other.

Often, third parties endure the losses in question. But indemnity clauses can also determine how to deal with losses endured by the contracting parties. An indemnity clause may require the indemnifying party to take over the defense of any lawsuits. Other times, it may require the indemnifying party to reimburse the other party for expenses covered by the clause.

To get a better idea of how indemnity works, imagine a baker has a contract to deliver 100 scones to a café. The contract states that the baker will indemnify the café for any claims by third parties arising from the baker’s negligence or breach of the contract. When a café patron gets sick from an undercooked scone and sues the café for damages, the café can require the baker to reimburse it for the costs it incurs in the suit or settlement.

When reviewing indemnity clauses, make sure your party is only responsible for losses caused by your own breaches or negligence. Or, if you must take responsibility for loss of your own property or injury to your workers caused by the counterparty’s negligence, make sure that the counterparty similarly takes responsibility for loss of its property or injury to its workers caused by your company’s negligence. If you’re required to reimburse the other party for expenses but not to take over the defense of lawsuits, make sure you have the right to veto any settlement offers. Keep in mind, too, that damages are not always caused by the actions of just one party. You may want to request a time limit on the indemnity obligation you could owe. For example, you could specify that your company will only indemnify the counterparty up to the amount or percentage of the damage that your actions directly caused.

Assignment

Assignment refers to the right of a party to transfer any or all of its rights or obligations under an agreement to a third party. For example, a baker may state it has the right to outsource packaging to another company. Typically, the party that drafts the contract reserves the right to assign its rights or obligations without obtaining the consent of the counterparty, and it prohibits the counterparty to assign any of its rights or obligations. But it’s more equitable to include the following phrase, which requires both parties to consent to assignment in a reasonable timeframe.

Neither Party may assign any of its rights or obligations under this Agreement without the consent of the other Party, whose consent shall not be unreasonably withheld or delayed.

When you draft or review an assignment clause, keep your needs in mind. What do you want your relationship with the counterparty to look like? Do you want the counterparty to be able to assign its right to receive payment to an affiliate? If your company is considering a future sale, you need to have the right to assign the agreement to a buyer after the merger. The assignment clause should also state that any assignment by a party that breaches the agreement is void.

Force Majeure

When an earthquake damages an entire region of a country or war breaks out where your company has operations, what happens to the affected contracts? Force majeure clauses protect parties when an act of God occurs, meaning an event which the affected party did not cause and over which they have negligible control.

When you draft or review force majeure clauses, the definition should not be too narrow or too broad. If too narrow, the clause will not capture many of the possible circumstances in which you have no control. If too broad, the counterparty could use the weakly defined clause to unreasonably excuse itself from performance.

Such clauses often (and always should) prohibit a party from claiming force majeure when the party is unable to pay balances due under the agreement regardless of the cause of the lack of funds.

When reviewing a force majeure clause, ensure the language doesn’t allow claims of force majeure for instances when the affected party could use reasonable efforts to remedy the situation. For instance, you may not want to allow labor strikes in general to be force majeure events because a party could attempt to escape a contract due to a strike at a single factory. Instead, you may want to limit force majeure events to industry-wide strikes.

Additionally, most force majeure clauses provide a time limitation for the event, after which one or either party can terminate without liability. For instance:

If a Force Majeure event lasts longer than ninety consecutive calendar days, then either Party may terminate the Agreement immediately upon written notice to the other Party.

No Waiver

No waiver clauses protect a party who waives—or forgives—a breach of the other party by preserving the non-breaching party’s right to enforce the contract in the future. A waiver is a knowing, intentional relinquishment of a contractual right. For example, a baker may accept a late payment by a restaurant for its scone delivery in June. But the no waiver clause allows him to enforce the payment terms in July if the restaurant fails to pay on time again.

A no waiver clause essentially says that if one party waives or forgives a breach, the waiver does not automatically waive all future breaches. It prohibits the restaurant, for instance, from arguing that because the baker permitted late payment once, all future payments can be late without consequence.

Merger

Also known as the integration or entire agreement clause, the merger clause prevents a party from claiming that part of the agreement was left out of the written contract and should still apply. The merger clause states that the written agreement encapsulates the entire agreement between the two parties, and that only what is written in the agreement is valid. For example, a baker may verbally agree to provide 10 free scones for every 100 scones purchased by a restaurant. But if the contract doesn’t mention the free scones, the merger clause prevents the restaurant from later claiming that the baker owes it a certain number of free scones.

Limitation of damages

The limitation of damages clause caps the total amount a party can owe the other party under the agreement. It may state a dollar figure or stipulate a multiple of the total contract amount. For master service or supply agreements, the liability for each service or purchase order is sometimes limited by the value of each service or purchase order. For example, a master supply agreement between a restaurant and a baker may govern all purchases of scones for the next two years and limit the liability of the baker for each purchase of scones to the total value of each purchase order. Then if the restaurant suffers damage from a particular batch of scones, the baker’s liability is limited to the value of the purchase order for those scones.

Generally, the limitation of damages clause limits only the liability owed by the party that drafted the agreement. When determining an appropriate upper limit, consider the value of the contract, the value of the relationship, the general risk of your liability under the contract, your insurance coverage, and how much financial risk you think is reasonable to bear given those factors.

Warranty

Warranty clauses limit the types of warranties a company provides and prohibit claims for damages not directly caused by the manufacturer or supplier. Warranty remedies include repair, replacement, credit, or reimbursement and are limited to a specific time frame after delivery.

It’s essential to carefully draft and review warranty clauses because a company can become liable for excessive warranty repair costs. If your company provides the warranty, make sure that the decision whether to reimburse, repair, credit, or replace belongs solely to you. Disclaim damage caused by normal wear and tear or the negligence of the buyer. And retain the right to investigate warranty claims to ensure the buyer did not cause the damage. If your company is a supplier or retailer of goods, limit the warranties you provide to those given to you by the manufacturer.

Confidentiality

A counterparty can freely share any information your company shares with it unless you have a nondisclosure agreement (NDA) or confidentiality provision in place. Think of all the types of information your company will share and which ones are important for you to protect, for instance, client lists, financials, or the existence of the agreement. Consider how long you need the confidentiality obligation to last based on the information. Will you be adequately protected if the confidentiality provisions apply only during the term of the agreement? Or does the confidentiality clause need to survive several years after the contract expires or terminates? Be sure to include a provision stating that the confidential information you share can only be used for purposes of the agreement.

Severability

A severability clause retains as much of the spirit and intent of the contract as possible if newly enacted legislation or an arbiter voids one or more of the contract’s provisions. Instead of allowing the voided clause to void the entire agreement, the severability clause states that the rest of the contract must remain intact and be read as though the voided provision is nonexistent.

Termination

While no one enters a business relationship expecting it to end early, it’s necessary to prepare in case it does. The termination clause states the reasons either party can dissolve the contract before the end of the contract’s stated term. It should also lay out the steps each party must follow upon termination and state how to allocate the costs arising from early termination.

Often, the drafting party gives itself the right to terminate for convenience without liability or provides numerous instances in which it can terminate while significantly limiting the counterparty’s ability to terminate. But for the non-drafting party, it may be preferable to ensure that the termination clauses are as mutual as possible. Require the counterparty to provide written notice of breach and stipulate a reasonable cure period to allow your company sufficient time to attempt to cure any breaches before the counterparty can terminate.

Conclusion

Boilerplate provisions may be standard, but they’re not one-size-fits-all. They demand your scrutiny, regardless of the number of times you’ve seen or drafted them.