The Impact of Coronavirus on Businesses

In addition to its human toll, the current coronavirus outbreak has wreaked havoc on global supply chains and commodities markets. With the virus’s rapid spread, the extension of the Lunar New Year holiday by the Chinese government, and transportation disruptions leaving hundreds of millions of workers unable to return to work (among other things), many Chinese businesses are struggling to fulfill their contractual obligations.

As of today, the China Council for the Promotion of International Trade has issued over 4,300 force majeure certificates covering a total of 330.8 billion Chinese yuan (US$47.2 billion) worth of goods now subject to cancellation or delay. The certificates acknowledge the outbreak as a force majeure event and absolve the recipient businesses from liability for non-performance or partial performance under relevant contracts, paving the way for them to succeed in their declarations that a force majeure has occurred in relation to their contracts.

Major Chinese companies that have recently claimed force majeure include: China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), the country’s largest importer of liquefied natural gas (LNG); Guangxi Nanguo, a copper smelter with an annual production capacity of 300,000 tonnes; and Jiangsu New Times Shipbuilding, a shipbuilder with an annual production capacity of 5 million deadweight tonnes (DWT). CNOOC’s claims have been rejected by Shell and Total, indicating that Shell and Total will seek compensation for CNOOC’s requested reduction in LNG deliveries; the outcome remains to be seen for the notices dispatched by Guanxi Nanguo and Jiangsu New Times Shipbuilding. Businesses in other countries are also evaluating whether to invoke the force majeure provisions in their contracts. For example, inquiries regarding declaring force majeure have arisen in Singapore. With one of the highest number of coronavirus cases outside of China, and as a result of quarantines and the rejections of work visas for hundreds of returning Chinese labourers, the Singaporean construction industry is experiencing labor shortages that firms expect may cause construction delays. International companies with operations in China and other affected countries have also experienced slowdowns and have taken measures like closing factories and stores whether due to the outbreak itself or its consequences, such as parts shortages.

Force Majeure in Contracts: Does Coronavirus Qualify?

Force majeure provisions in contracts establish the circumstances under which a party’s obligations under the contract may be suspended, or otherwise altered, due to events deemed to be out of the affected party’s control. Examples include natural disasters, acts of terrorism or war, acts of God, labor disruptions, or even pandemics. As we have previously noted, force majeure provisions are important because the occurrence of a force majeure event can result in any number of effects such as a party’s exemption from performing its contractual obligations (important to the non-affected party), potential notification requirements (important to the affected party), or even the possibility of terminating the contract altogether (important to all parties).

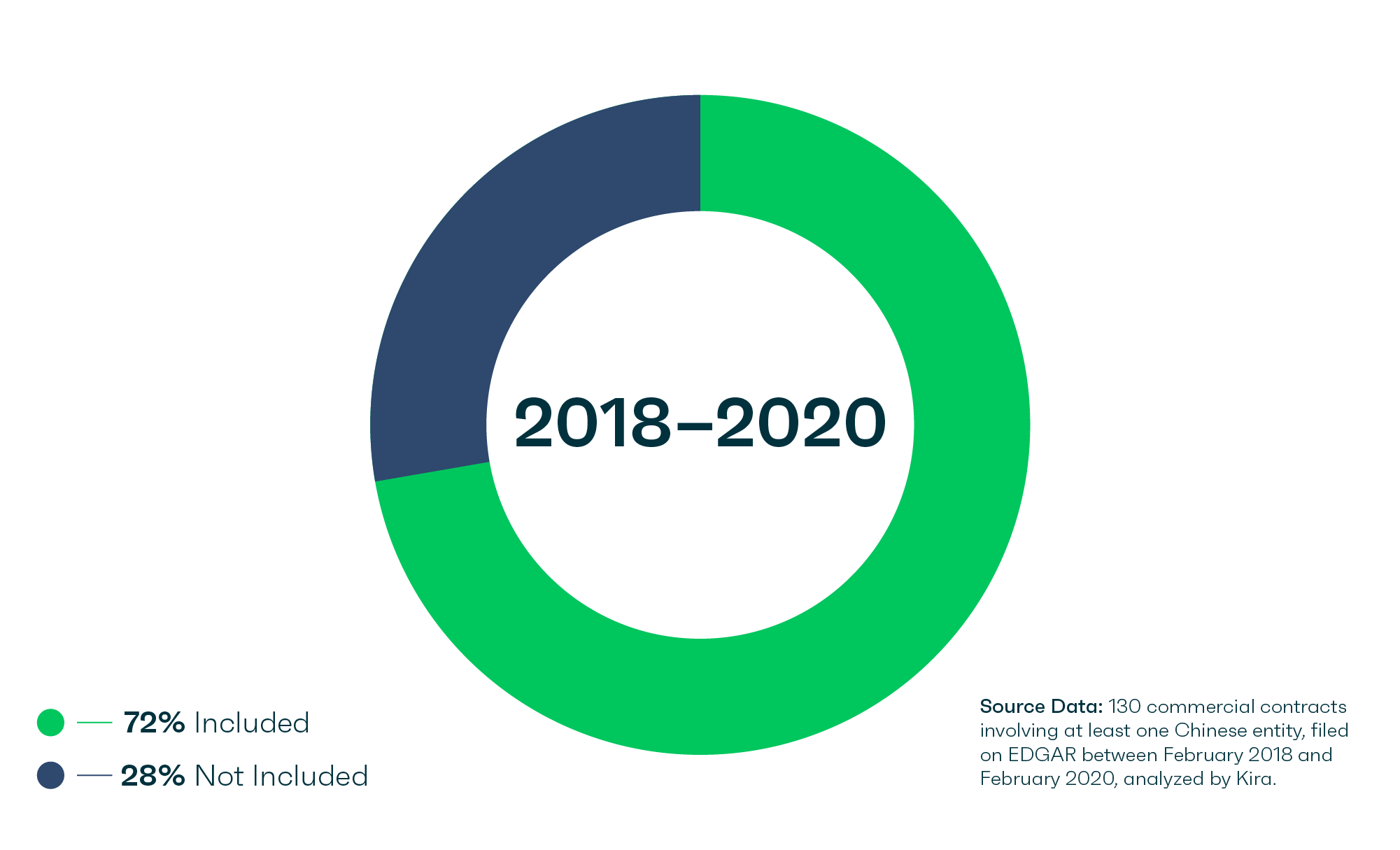

Unsurprisingly, whether the coronavirus outbreak counts as a force majeure event under a given contract depends on the wording of the force majeure provision in the contract. Due to this, we took a closer look at a sample set of contracts involving Chinese entities to better understand what they include with respect to force majeure. Within ten hours, we used Kira to review substantially all of the commercial contracts filed on EDGAR between February 2018 and February 2020 that involved at least one Chinese entity to determine: (1) the overall prevalence of force majeure provisions (with a separate analysis for loan and credit-related agreements); (2) the prevalence of force majeure provisions that expressly include public health-related events in the definition of force majeure; (3) the prevalence of force majeure provisions that include either broader “catch-all” language in the definition of force majeure or public health-related events in the definition of force majeure; and (4) the prevalence of force majeure provisions including acts of government in the definition of force majeure.

Kira Insights: Force Majeure Provisions in Chinese Contracts

Our analysis in Kira indicated that many of the contracts provided for procedures to be followed in the event of a force majeure occurrence. Out of the 130 contracts, 72% included force majeure provisions.1

1 Even if a force majeure provision is not included, or the coronavirus does not otherwise qualify as a force majeure event, the Chinese law doctrine of “changed circumstance” may apply to modify or invalidate the contract.

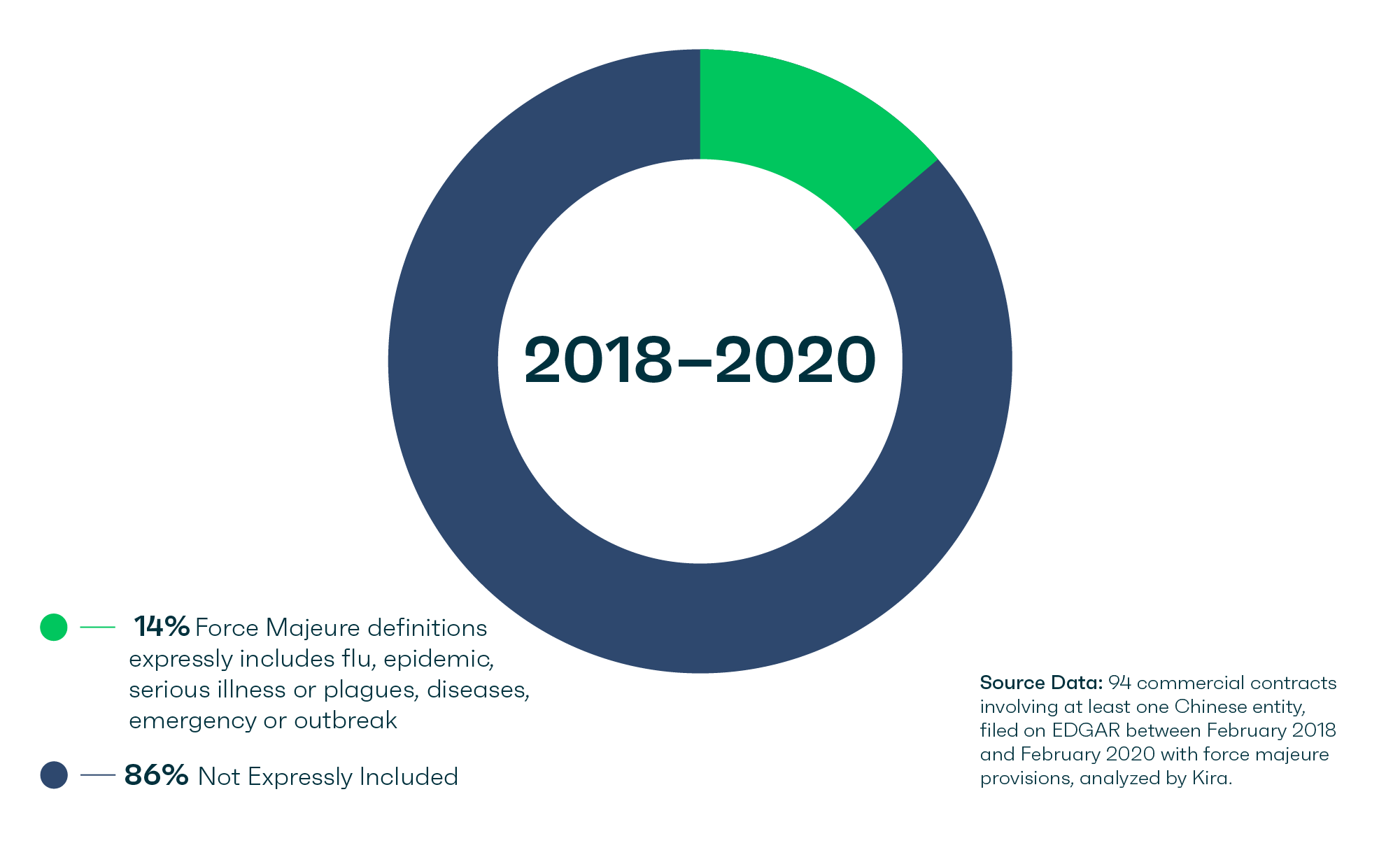

Public Health-Related Events in Force Majeure Provisions

Force majeure provisions do not often specify public health-related events as force majeure events. As we expected to find, out of the 94 contracts with force majeure provisions, 13 of them included force majeure provisions explicitly stating that public health events such as flu, epidemic, serious illness or plagues, disease, emergency or outbreak would constitute a force majeure situation.

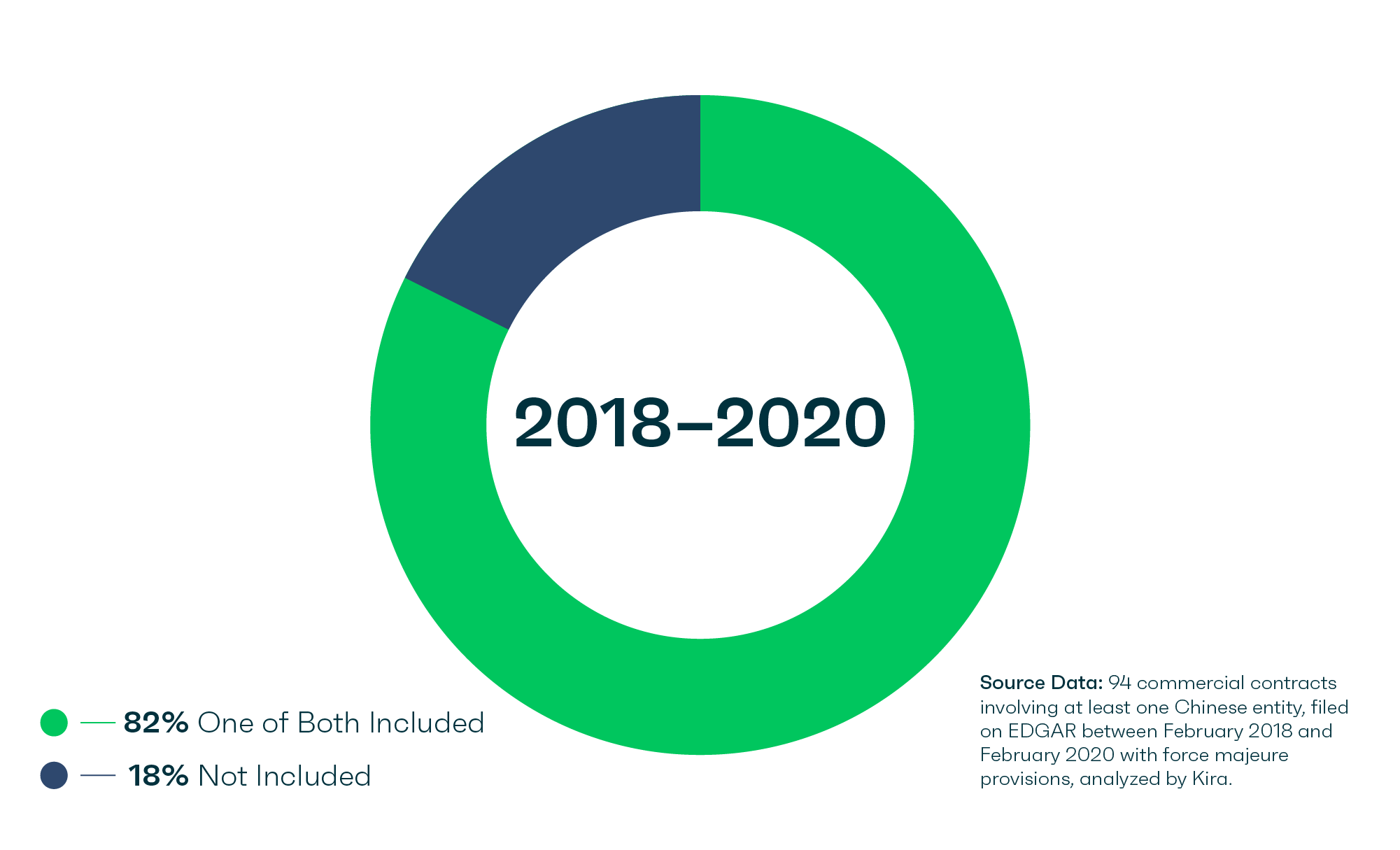

“Catch-All” Language in Force Majeure Provisions

A larger portion of the contracts included “catch-all” language in the force majeure provisions. Catch-all language states that “any other events that cannot be predicted and are unpreventable and unavoidable by the affected [p]arty,” constitute force majeure. Of the 94 contracts with force majeure provisions, 82% either incorporated catch-all language or specifically enumerated public health-related events as described above in the definition of force majeure.

Acts of Government

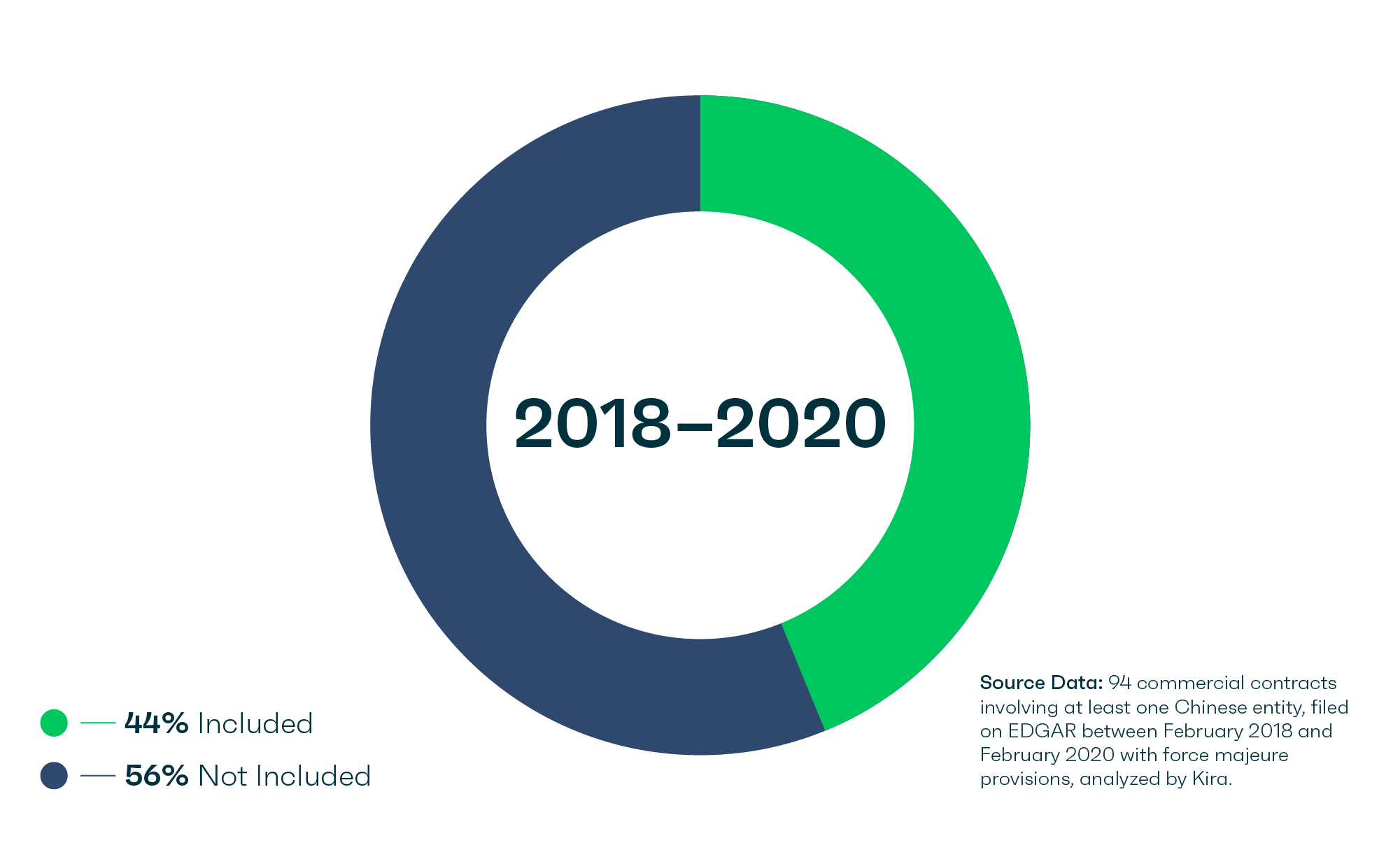

A significant portion of the force majeure provisions also stated that acts of government would qualify as force majeure events that would excuse an affected party’s non-performance. Of the 94 contracts including force majeure provisions, 44% included acts of government in the definition of force majeure.

Conclusion

With the severity and prevalence of the coronavirus escalating quickly, and more businesses and industries affected each day–from auto parts supply to meat imports to wedding gowns –the volume of contracts that may warrant review for force majeure provisions is growing. Businesses dealing with affected entities should:

- Review all relevant contracts for force majeure provisions that mention or include: public-health related events; government acts; and/or “catch-all” language in order to anticipate whether those contracts may be affected by the coronavirus outbreak, so the parties can begin to develop a plan to mitigate any related losses.

- In drafting commercial contracts going forward, consider including events such as epidemics, outbreaks or pandemics in the definition of force majeure to avoid ambiguity.

The full text of our study includes additional data points and more in-depth commentary, including a separate analysis for loan and credit-related agreements. If you would like to read further about the usage of force majeure provisions in Chinese contracts, access the full report.